On a rocky precipice above the Green River in present east central Utah, one man struggled to save another from falling hundreds of feet. Suspended by a pair of long underwear, the endangered man had only one arm. All he could do was hang on with his left hand until his companion pulled him to safety. The date was July 8, 1869. The one-armed man was John Wesley Powell, director of the Colorado River Exploring Expedition.

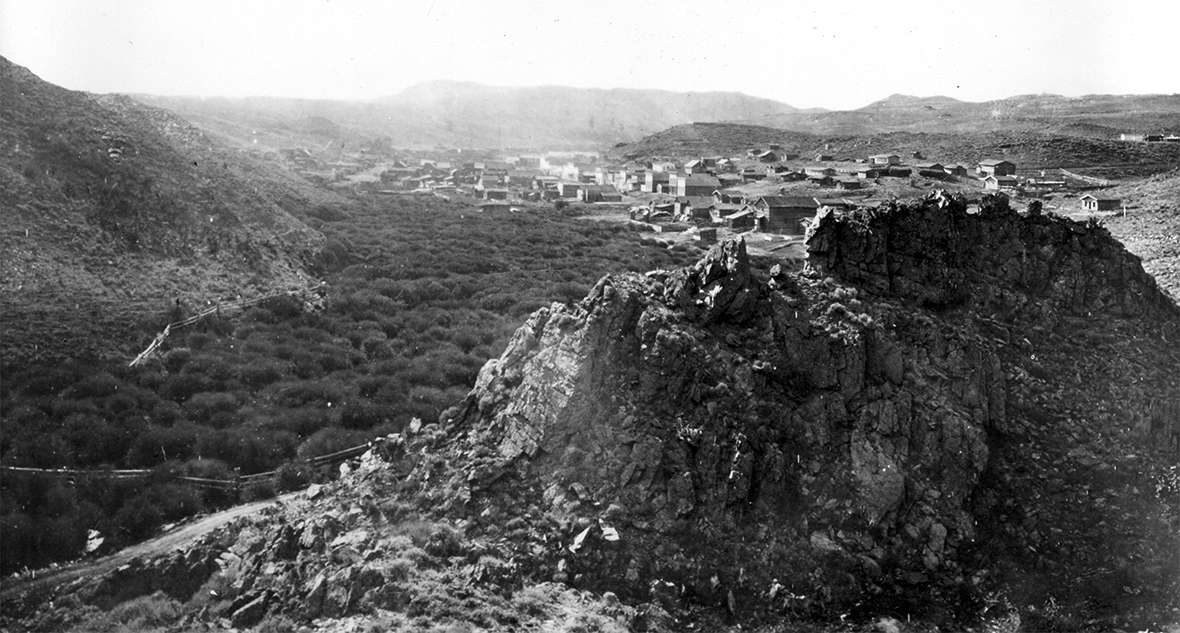

![An artist’s version of Powelll’s dramatic rescue in the Grand Canyon, July 1869. Scribner’s Monthly. An artist’s version of Powelll’s dramatic rescue in the Grand Canyon, July 1869. Scribner’s Monthly.]() About six weeks previously, the party had launched its boats from the town of Green River on the Union Pacific Railroad in Wyoming Territory. They planned to follow the Green River to where it joins the Colorado River in present southeast Utah. From there, Powell hoped to float all the way to the junction of the Virgin and Colorado rivers, about 20 miles past the eastern end of the Grand Canyon in present Arizona. The heart of this region was the last in the continental United States unknown to Euro-Americans. Although the trip would have been a daring exploit for any man, Powell was intent not on adventure—but science.

About six weeks previously, the party had launched its boats from the town of Green River on the Union Pacific Railroad in Wyoming Territory. They planned to follow the Green River to where it joins the Colorado River in present southeast Utah. From there, Powell hoped to float all the way to the junction of the Virgin and Colorado rivers, about 20 miles past the eastern end of the Grand Canyon in present Arizona. The heart of this region was the last in the continental United States unknown to Euro-Americans. Although the trip would have been a daring exploit for any man, Powell was intent not on adventure—but science.

Initially known as an explorer, Powell pursued his main passion of science, especially geology and ethnology, throughout his career. He helped to start the United States Geological Survey, became its second director, and conceived a unique and comprehensive vision for managing the lands and limited water of the arid West. This placed him among the social and scientific innovators of his age, and his influence on the development of the West continues far beyond his lifetime.

Early life and education

Powell was born in Mount Morris, N.Y., on March 24, 1834, to British Methodist immigrants Joseph and Mary Powell. He attended schools in Ohio and Wisconsin, where his parents purchased farms, but his primary pre-college education was outdoors in the company of knowledgeable neighbors and friends of the family who became his science tutors.

Between 1853 and 1858, Powell attended three colleges in Illinois and Ohio, but never earned a degree. He joined the new Natural History Society of Illinois, becoming its secretary in 1858. Between terms of college, he spent summers exploring and made various solitary river excursions on the Mississippi River and its tributaries.

The Civil War and beyond

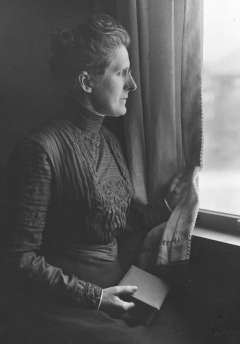

Powell enlisted in the Union Army in May 1861, just a month after the outbreak of the Civil War. Late that fall, he took a quick leave to marry his half-cousin, Emma Dean, in Detroit on Nov. 28. At the Battle of Shiloh on April 6, 1862, he lost his right forearm, but after recovering, continued to serve until Jan. 4, 1865, when he was discharged. This was three months before the end of the war, but he was exhausted after helping to oversee the successful defense of Nashville, Tenn. He left the Army as a brevet colonel, though he preferred the title, major, and would be known by that the rest of his life.

Later that year, Powell was appointed professor of science at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington, Ill. In 1867, he left that post to become curator of the Illinois Natural History Museum at the Illinois State Normal University, also in Bloomington.

First western expeditions

That summer, Powell organized his first western expedition to the Rocky Mountains in present Colorado. Funding from Illinois State Normal University, the Illinois Industrial University in Urbana and the Chicago Academy of Science totaled $1,100. In addition, Ulysses S. Grant, Powell’s former commander in the Civil War, authorized Powell to purchase rations from military commissaries at low rates.

![Emma and John Wesley Powell in Detroit, 1862. Earlier that year, Powell lost most of his right arm at the Battle of Shiloh. Wikipedia. Emma and John Wesley Powell in Detroit, 1862. Earlier that year, Powell lost most of his right arm at the Battle of Shiloh. Wikipedia.]() His wife, Emma, the party’s ornithologist and the only woman in the group, proved as hardy as the men; when the party climbed the rough trail up Pike’s Peak on July 27 and 28, she kept up easily. She went along the next year as well on Powell’s second and longer expedition, again through the Rocky Mountains and this time across the western slope. During these two journeys, Powell began to plan his trip down the Green and Colorado Rivers for spring and summer 1869.

His wife, Emma, the party’s ornithologist and the only woman in the group, proved as hardy as the men; when the party climbed the rough trail up Pike’s Peak on July 27 and 28, she kept up easily. She went along the next year as well on Powell’s second and longer expedition, again through the Rocky Mountains and this time across the western slope. During these two journeys, Powell began to plan his trip down the Green and Colorado Rivers for spring and summer 1869.

The 1869 voyage

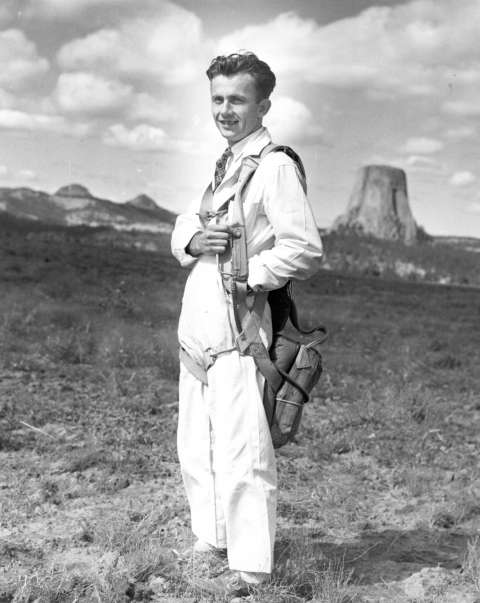

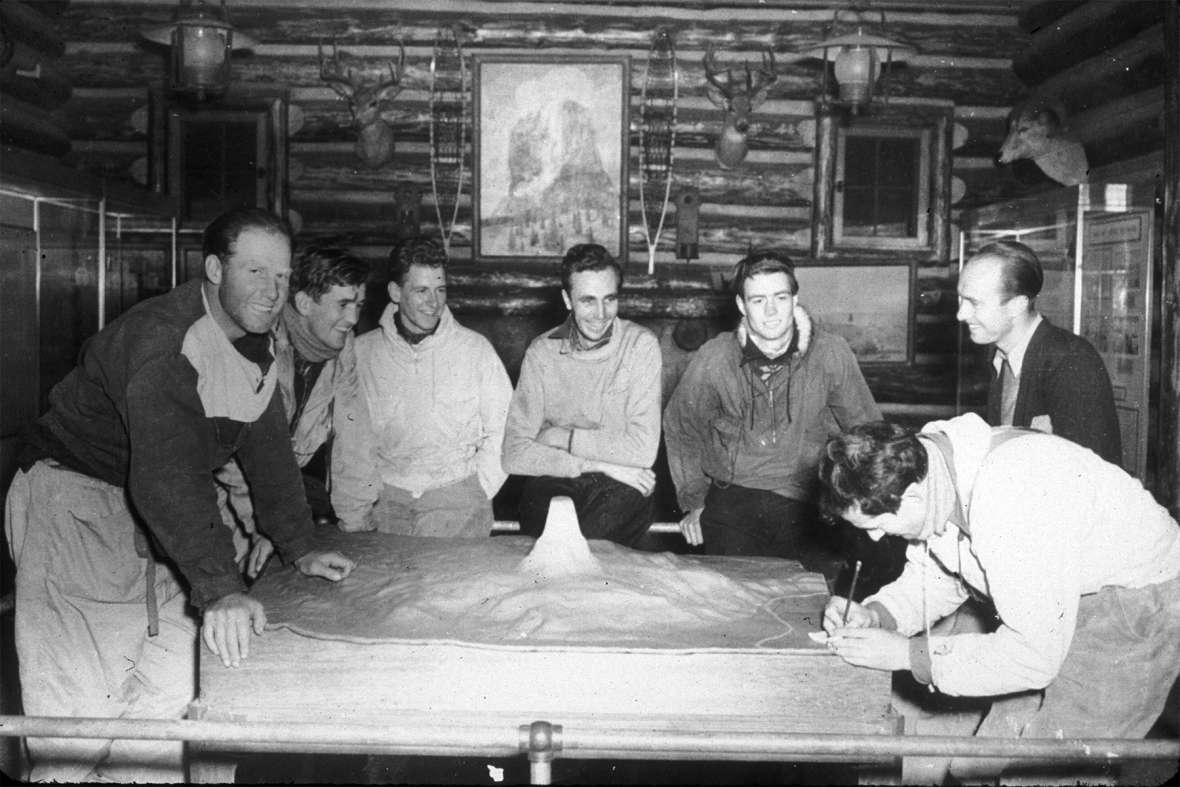

On May 24, 1869, Powell and his group of nine men launched their four boats into the Green River directly off a Union Pacific flatbed railroad car. One boat was pine, 16 feet long, relatively small and light; designed to be the pilot boat. The other three were oak, 21 feet long, four feet wide and two feet deep. These were to carry most of the expedition’s supplies.

Though the expedition had some important logistical support from the U.S. Army, it was by no means a government-funded effort. Support came from a variety of sources: funds from the Illinois Natural Historical Society, Illinois Industrial University, other private sources and Powell’s own pocket; scientific instruments from the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. and the Chicago Academy of Science; low-priced or free rations from western military posts, approved by Congress; and free transportation of the boats from Chicago to Green River, apparently courtesy of the railroads.

Months after starting, after many hardships and accidents, six men and two boats emerged from the mouth of the Grand Canyon. They reached the Virgin River on Aug. 30, 1869. One man had left the expedition after the first month, and three more had climbed out of the canyon near the end of the journey only to be killed, possibly by a band of Shivwits Paiute Indians, or possibly by Mormons. Powell biographer Donald Worster dismisses the latter idea as unlikely. The expedition had taken about three months, much less than the 10 months to a year Powell predicted. No white explorer had ever before completed the route, and possibly no tribal people, either.

![Temporary and permanent Union Pacific Railroad bridges at the town of Green River, Wyoming Territory, 1868. For his expeditions down the Colorado in 1869 and 1871, Powell, his crews and their boats took the train to Green River and launched from there. A.J. Russell photo. Temporary and permanent Union Pacific Railroad bridges at the town of Green River, Wyoming Territory, 1868. For his expeditions down the Colorado in 1869 and 1871, Powell, his crews and their boats took the train to Green River and launched from there. A.J. Russell photo.]()

The Powell Survey

Powell’s success catapulted him to nationwide fame. Seemingly overnight, he became an authority on the American West. After arriving in Salt Lake City, Utah Territory, in mid-September 1869, and delivering his first lecture on the expedition, reported by the September 15 Deseret Evening News, Powell took the train home to Illinois. On September 28, The Chicago Tribune described Powell as “Your unassuming but brave and accomplished explorer.” Soon thereafter, Powell spoke about his expedition to crowds at the Chicago Academy of Science, in Cincinnati, Ohio, Wheaton, Ill. and Brooklyn, N.Y.

On July 12, 1870, Congress appropriated $12,000 for Powell to survey the lands adjoining the Colorado River and its tributaries. The Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, later known as the Powell Survey, was the third of the major western scientific surveys, including those already in progress led by Ferdinand Hayden and Clarence King. Powell’s and Hayden’s civilian surveys were run under the General Land Office of the Department of the Interior. King’s, though also a civilian survey, was supported by the War Department, under the Treasury. Army Lt. George M. Wheeler launched a fourth, and military, survey in 1871.

Under these auspices, Powell made a second expedition down the Green and Colorado Rivers, again with a launch in Green River, Wyoming Territory and with a photographer this time, in 1871.

All four surveys—generally small parties of a dozen or two men—gathered information on the geography, minerals, agricultural prospects, topography, water resources and geology of the West and issued regular reports on their work, often lavishly illustrated with maps and photographs. Mostly they spent summers in the field, and winters organizing their information. Powell’s survey expeditions often stretched into October or November. In 1872-1873, three members of his crew wintered in Kanab, Utah Territory, living in tents and working on their maps.

On April 1, 1878, Powell, after eight years of work, presented the results to the commissioner of the General Land Office: “Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States With a More Detailed Account of the Lands of Utah.” This document articulated Powell’s plan, including two proposed bills, for how the West should be developed. He held this point of view for the rest of his life.

Powell disagreed with the boosters and promoters of his day. Powell biographers Wallace Stegner, Donald Worster and John Ross all mention William Gilpin, first governor of Colorado Territory in 1861, as a popular promoter of the unlimited possibilities of the West, in farming, ranching, mineral development and timber exploitation. According to Gilpin’s widely accepted view, vision and hard work were enough to transform the whole West into a paradise of economic prosperity, without regard for the realities of climate or terrain.

![Powell thought of the West in terms of its scarce water as well as its lands. Here, his map of the region’s watersheds, from 'Report on the Lands of the Arid Regions …', 1878. Mapped in Wyoming Territory are the drainages of the Yellowstone (dark olive), Missouri (orange), North Platte (pale pink), Green (red and pink) and Snake (blue) rivers. John F. Ross collection. Click to enlarge Powell thought of the West in terms of its scarce water as well as its lands. Here, his map of the region’s watersheds, from 'Report on the Lands of the Arid Regions …', 1878. Mapped in Wyoming Territory are the drainages of the Yellowstone (dark olive), Missouri (orange), North Platte (pale pink), Green (red and pink) and Snake (blue) rivers. John F. Ross collection.]() Powell stated in the Arid Lands Report that only a small fraction of the West could be irrigated and farmed. He further concluded in the Report that the land survey system in place on government lands since the early 1800s, based on grids of sections one mile square surveyed into townships six miles square, did not serve western homesteaders. One quarter-section might contain all the water for miles around, leaving the person who owned that parcel in sole control of the water, while his neighbors hoped for rain and tried not to starve in the meantime.

Powell stated in the Arid Lands Report that only a small fraction of the West could be irrigated and farmed. He further concluded in the Report that the land survey system in place on government lands since the early 1800s, based on grids of sections one mile square surveyed into townships six miles square, did not serve western homesteaders. One quarter-section might contain all the water for miles around, leaving the person who owned that parcel in sole control of the water, while his neighbors hoped for rain and tried not to starve in the meantime.

Thus, Powell proposed in the Arid Lands Report, “[A] general law should be enacted under which a number of persons would be able to organize and settle on irrigable districts and establish their own rules and regulations for the use of the water and subdivision of the lands.”

The New-York Daily Tribune of April 4, 1878, reviewed Powell’s report, as did The Nation on May 2. Both reviews were favorable; the Tribune quoted long passages from the Report, and The Nation offered commentary and discussion. In early April, Congress ordered that the report be printed. Powell distributed as many copies as possible to the press and to influential people outside of Congress. California Democratic Congressman Peter Wigginton introduced Powell’s two proposed bills into the House Committee on Public Lands, and at the beginning of the next session Powell introduced revised versions into the committee. The bills progressed no further, however, because, writes biographer Worster, most committee members did not support Powell’s views.

The United States Geological Survey

In 1879, Congress consolidated the staff, efforts and funding of the four western surveys into the United States Geological Survey within the Department of the Interior, appointing Clarence King director. Powell became director of the new Bureau of Ethnology. His job was to organize data he had collected on the western and southwestern Indian tribes he had observed during the years of his survey.

On March 11, 1881, shortly after King resigned, possibly due to ill health, President James A. Garfield appointed Powell the second director of the USGS, a position he held along with the directorship of the Bureau of Ethnology for most of the rest of his public career. His mission was part economic, part pure science. For example, he continued many of the survey’s geological studies centered on exploitable mineral resources, but also funded paleontology research.

On Oct. 2, 1888, after years of expanding the USGS, Powell obtained $100,000 from Congress for the USGS to begin a massive irrigation survey. The following year, Congress added an additional $250,000 for this project. Its purpose was to map in detail all the water sources and their drainages in the United States, with special priority for those in the West. The resulting map would identify which regions were viable for settlement, according to where the water was, and help to realize Powell’s vision of a fair and realistic plan for the people using that water.

The original funding authorization included a paragraph temporarily prohibiting settlement on known irrigable lands, reservoir sites and ditch sites. This was primarily the work of Colorado Rep. George Symmes, who had watched speculators in his state take away water before small farmers could get to it. The prohibition was not immediately enforced.

Once the mapping was complete, all land could be classified. Non-irrigable areas would be closed to homesteaders, preventing the failure of impoverished settlers who hoped to earn a farm by their hard work alone. Under the Homestead Act of 1862, any male or female citizen could gain ownership of a 160 acre homestead by living on it for five years and improving it, although in the West, 160 acres was not enough to support a household or even a single owner.

As Symmes and other Western congressmen feared, hordes of speculators, ready to monopolize all the water, followed the surveyors. Donald Worster notes that in New Mexico, the Pecos Valley Irrigation and Investment Company, one of many, had spent a million dollars to dig two large canals. The July 1889 Idaho constitutional convention reported to U.S. Interior Secretary John W. Noble that a huge crowd of speculators had filed illegal land claims in the wake of irrigation surveyors in the Bear Lake area in the southeast corner of the territory.

Noble replied to George L. Shoup, governor of Idaho, “This is the law of today, unreserved, unrepealed, and in full force. … It follows necessarily that the speculators, corporations, or other persons referred to … are under the effect of this law and unable to obtain the advantages that you say they are seeking.”

Noble also directed the Commissioner of the General Land Office to enforce the law, and asked William Howard Taft, solicitor general of the Interior Department, for a ruling on the problem. Taft recommended the temporary closure of all public lands in the West.

This decision was a rude shock to the thousands of people who had filed for western homesteads since Oct. 2, 1888, the date of the original prohibition; those filings were now null and void. Many others wanted to stake a claim anywhere, regardless of what was known about water in their chosen quarter-section. Speculators were also nettled; Worster reports that Powell received letters from individuals and corporations complaining that they could not access land or water. Senators from North and South Dakota claimed that their constituents were being mistreated.

Powell’s political enemies pounced, even though he had authored neither the original decision nor Taft’s recommendation. Sen. William Stewart of Nevada was particularly aggressive, and in part due to his attacks, with others joining in, Congress cut all funding to the irrigation survey in late August 1890, at the same time reopening land for settlement. The irrigation survey had lasted slightly less than two years.

Allocating water

On his first and Colorado River trips and on subsequent overland survey expeditions, Powell noticed elementary facts about his study area, many recorded in his Arid Lands Report, that influenced his thinking from that time forward. For example, though a huge volume of water flowed in the Green, Grand (the former name for the upper Colorado) and Colorado rivers, most of the adjoining land was hundreds of feet higher than all that water, and hence could not be irrigated with it.

The level of detail in the Arid Lands Report, and its extensive scope, show that Powell thought long and hard about how the limited water in the West could be managed fairly and efficiently. He seems not to have tackled the question of who should pay for the ditches, canals and small reservoirs he envisioned.

![John Wesley Powell at his desk in Washington, D.C., in 1896. Under intense pressure from his political enemies, he had resigned his directorship of the U.S. Geological Survey two years earlier, but stayed on as head of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology. Wikipedia. John Wesley Powell at his desk in Washington, D.C., in 1896. Under intense pressure from his political enemies, he had resigned his directorship of the U.S. Geological Survey two years earlier, but stayed on as head of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology. Wikipedia.]() For the logistics of development, he stated in the Report that small, local water districts were best. He proposed self-governing, cooperative groups of about nine ranches or farms whose occupants actually used the water. He further recommended political divisions, such as county lines, based on watersheds and the resulting use of water in those areas. Non-irrigable areas, he decided, should not be settled.

For the logistics of development, he stated in the Report that small, local water districts were best. He proposed self-governing, cooperative groups of about nine ranches or farms whose occupants actually used the water. He further recommended political divisions, such as county lines, based on watersheds and the resulting use of water in those areas. Non-irrigable areas, he decided, should not be settled.

These were his most radical ideas, and unpopular, because so many could not accept the suggestion of limiting development. As people pushed west in ever-increasing numbers, some of them, at least, carried along a persistent vision of unlimited prosperity and growth. William Gilpin, for example, certainly inflated a great many hopes with his claims that the American West was “the most attractive, the most wonderful, and the most powerful department of their continent, of their country, and of the whole area of the globe.”

Powell, always swimming against this current of opinion, was undaunted, but also unsuccessful. The irrigation survey could not continue without funding. His entire plan for water-centered settlement depended on the accurate identification of watersheds, the volume of water in individual rivers or streams and other data only that project could establish.

In the spring of 1894, Powell resigned from the USGS, but retained his position at the Bureau of American Ethnology, as it had been renamed. In daily life, Powell faced some formidable obstacles, including chronic severe pain from his amputation, and the need to dictate to a stenographer every word he published. But, he did not let these problems deter him, nor even, for a long time, slow him down. He died at the family cottage in Haven, Maine, on Sept. 23, 1902, of a cerebral hemorrhage following a stroke eight months earlier, from which he had never fully recovered. Emma was present with Mary, their only child, then 31 years old.

Powell’s legacy

![A stamp issued in 1969 commemorated the 100th anniversary of Powell’s first descent of the Green and Colorado rivers. May 24, 2019, marks the 150th anniversary of his launch. Wikipedia. A stamp issued in 1969 commemorated the 100th anniversary of Powell’s first descent of the Green and Colorado rivers. May 24, 2019, marks the 150th anniversary of his launch. Wikipedia.]() About three months before Powell died, on June 17, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Newlands Reclamation Act into law. This created the United States Reclamation Service, now known as the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Continuing the work of the USGS Irrigation Survey, bureau staff mapped all the major watersheds in the West by 1951.

About three months before Powell died, on June 17, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Newlands Reclamation Act into law. This created the United States Reclamation Service, now known as the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Continuing the work of the USGS Irrigation Survey, bureau staff mapped all the major watersheds in the West by 1951.

The Bu Rec has built many huge dams, and although water policy in the West has not, on the whole, followed Powell’s plan for sustainable use and development, the imprint of his vision remains. For example, modern-day grazing and irrigation districts aim to benefit and involve those who use those areas, according to the capabilities of the land. One contemporary writer believes that some of Powell’s ideas, had they been implemented, could have prevented the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. Of that debacle, John F. Ross states, “Too many settlers had pushed the land beyond its capacity, just as Powell had predicted.”

Powell’s influence also shows in the accomplishments of Elwood Mead, Wyoming’s first territorial engineer, or chief government water officer. Thanks to Mead’s efforts, water rights in Wyoming belong to the state and then are appropriated to users through a system of permits.

As a result, water rights in Wyoming go to the user, not to the speculator or settler who arrived first and didn’t stay, or tried to appropriate more water than he could use. Furthermore, in the State Engineer’s Biennial Report for 1915-1916, Mead and other officials recommended the development of a water district on the Green River drainage, similar to Powell’s proposals.

Above all, Powell was a man not just of action, but of vision. He presented his ideas with clarity and force, and although some were smashed in political battles or in the conflict between ideologies of moderate and excessive development, this does not diminish the magnitude of his achievements.

Resources

Primary Sources

- “Academy of Sciences: A Field Day Among Geologists.” New-York Daily Tribune, April 28, 1877. Chronicling America. Library of Congress. Accessed Nov. 14, 2018, at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1877-04-28/ed-1/seq-5/.

- Arid Lands in the West: Major Powell’s Report.” New-York Daily Tribune, April 4, 1878. Chronicling America. Library of Congress. “Accessed Nov. 14, 2018, at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1878-04-04/ed-1/seq-5/.

- Congressional Record.July 26, 1890. 7781. Accessed Dec. 12, 2018, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1890-pt8-v21/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1890-pt8-v21.pdf.

- “Exploration of the Colorado Finished.” The Deseret Evening News, Sept. 15, 1869. Accessed Dec. 12, 1869, at https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s64x96x2/23155393.

- “A Lecture by Major Powell on the Colorado Canon.” The Chicago Tribune, Sept. 28, 1869. Chronicling America. Accessed Dec. 12, 2018, at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014064/1869-09-28/ed-1/seq-2/.

- “Our Unavailable Public Lands.” The Nation, May 2, 1878. Google Books. Accessed Nov. 2, 2018, at https://books.google.com/books?id=Fek4AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA288&lpg=PA288&dq=%22our+unavailable+public+lands%22&source=bl&ots=vR0Axvq1sY&sig=9Y3oduRUV0Txm17qnrE9pD4qExY&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjika2TirTeAhU0On0KHcD-Cb0Q6AEwAnoECAAQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22our%20unavailable%20public%20lands%22&f=false.

- Powell, John Wesley. The Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyons. 1895. Canyons of the Colorado.Reprint. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2002, 73-111.

- ________________. Report on the Arid Region of the United States With a More Detailed Account of the Lands of Utah. Edited by Wallace Stegner. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1962, 11-57.

- Thirteenth Biennial Report of the State Engineer to the Governor of Wyoming, 1915-1916, Laramie, Wyo.: The Laramie Republican Company Printers and Binders, 1916, pp. 54-55, 62-63. Also accessible at Hathi Trust Digital Library, accessed Dec. 6, 2018, athttps://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015011420521;view=1up;seq=9.

- Wyoming Newspapers. Accessed Oct. 23, 2018, Nov. 14, 2018, at newspapers.wyo.gov:

- Cheyenne Daily Leader, May 6, 1870; May 31, 1870; Aug. 10, 1870; April 25, 1871; May 8, 1871; May 7, 1873.

- The Cheyenne Leader, May 25, 1869.

- The[Cheyenne] Daily Evening Leader, Sept. 18, 1869.

- The[Cheyenne] Daily Leader, Oct. 1, 1875.

- The [Cheyenne]Daily News, Sept. 13, 1875.

- Laramie Daily Sentinel, Feb. 23, 1872.

- The[Cheyenne] Wyoming Weekly Leader, May 8, 1869; July 3, 1869; July 17, 1869; July 24, 1869.

- [Cheyenne] Wyoming Weekly Leader, July 17, 1869.

Secondary Sources

- Darrah, William Culp, Ralph V. Chamberlin and Charles Kelly, eds. The Exploration of the Colorado River in 1869 and 1871-1872: Biographical Sketches and Original Documents of the First Powell Expedition of 1869 and the Second Powell Expedition of 1871-1872. Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, University of Utah Press, 2009, 46. First published 1947. Utah Historical Quarterly, 15.

- “Homestead Acts.” Wikipedia. Accessed Dec. 13, 2018, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homestead_Acts.

- “John Wesley Powell.” Wikipedia. Accessed Sept. 21, 2018, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Wesley_Powell.

- MacKinnon, Anne. “Order out of Chaos: Elwood Mead and Wyoming’s Water Law.” WyoHistory.org. Accessed Oct. 26, 2018, at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/order-out-chaos-elwood-mead-and-wyomings-water-law.

- Rea, Tom. Devil’s Gate: Owning the Land, Owning the Story. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006, 123, 124, 164-166, 184, 199.

- Robinson, Michael C. Water for the West: The Bureau of Reclamation 1902-1977. Chicago: Public Works Historical Society, 1979, 11, 12, 19.

- Ross, John F. “How the West Was Lost.” The Atlantic, Sept. 10, 2018. Accessed Nov. 27, 2018, at https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/09/how-the-west-was-lost/569365/.

- __________. The Promise of the Grand Canyon: John Wesley Powell’s Perilous Journey and His Vision for the American West. New York: Viking, 2018. Gilpin’s remark that the West was “the most attractive, the most wonderful, and the most powerful department of their continent,” p. 257.

- ———. “The Visionary John Wesley Powell Had a Plan for Developing the West, But Nobody Listened.” Smithsonian.com, July 3, 2018. Accessed Nov. 27, 2018, at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/visionary-john-wesley-powell-had-plan-developing-west-nobody-listened-180969182/.

- Stegner, Wallace. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West. New York: Penguin Books, 1992.

- Tanner, Russel R. “Leasing the Public Range: The Taylor Grazing Act and the BLM.” WyoHistory.org. Accessed Oct. 29, 2018, at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/leasing-public-range-taylor-grazing-act-and-blm.

- United States Department of the Interior. Brief History of The Bureau of Reclamation. 2000. Accessed Nov. 14, 2018, at https://www.usbr.gov/history/briefhis.pdf.

- Worster, Donald. A River Running West:The Life of John Wesley Powell. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Yochelson, Ellis L. “Monuments and Markers to the Territorial Surveys.”Annals of Wyoming 43, no. 1 (Spring 1971): 113-124. Accessed Sept. 28, 2018, at www.archive.org/details/annalsofwyom43121971wyom.

Illustrations

- The scan of the 1878 map of the arid regions is from the collection of historian John F. Ross. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Powell at his desk is from the Smithsonian via Wikimedia Commons. Used with thanks.

- The pair of wedding photos of John and Emma Powell and the image of the 1969 postage stamp are all from Wikipedia. Used with thanks. The photos of the Powells are from the National Archives and Records Administration, photo citation numbers 79-JWP-1 and 79-JWP-5.

- The picture of Powell’s dramatic rescue in the Grand Canyon is from a copy of Scribner’s Monthly vol. 9, 1874-1875, p. 305, originally digitized by Cornell University. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the locomotive on the UP railroad bridge is by A.J. Russell, from the collections of the Oakland Museum of California. Used with thanks.

“Here we found a great curiosity,” Mormon pioneer Norton Jacob wrote June 24, 1847. “[It] would seem that Vegetation & Frost had agreed to operate in copartnership, for in digging through a grassy turf to open a Spring we found plenty of Ice!”

“Here we found a great curiosity,” Mormon pioneer Norton Jacob wrote June 24, 1847. “[It] would seem that Vegetation & Frost had agreed to operate in copartnership, for in digging through a grassy turf to open a Spring we found plenty of Ice!”

Hague returned to the Yellowstone area for seven straight summers, with a growing field of study. He was well-traveled, with far-ranging interests. For example, he was the first to chronicle flecks of gold in the Stinkingwater Mining Region, at the confluence of Needle Creek and the South Fork of the Shoshone River southwest of present

Hague returned to the Yellowstone area for seven straight summers, with a growing field of study. He was well-traveled, with far-ranging interests. For example, he was the first to chronicle flecks of gold in the Stinkingwater Mining Region, at the confluence of Needle Creek and the South Fork of the Shoshone River southwest of present  The idea of expanded park borders was not new. In 1882 Gen. Phillip

The idea of expanded park borders was not new. In 1882 Gen. Phillip

The commission’s chair was botanist Charles Sprague Sargent, head of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum and publisher of Garden and Forest magazine. Its secretary was a young forestry graduate—at 31, half the average age of the other commissioners—named Gifford Pinchot. Also on board: Gen. Henry L. Abbot of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, a veteran of Western railroad surveys; Alexander Agassiz, curator at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology; Yale professor William H. Brewer, who was also California’s state botanist; John Muir, in an unofficial advisory capacity since he wasn’t the sort of person to join committees; and Arnold Hague.

The commission’s chair was botanist Charles Sprague Sargent, head of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum and publisher of Garden and Forest magazine. Its secretary was a young forestry graduate—at 31, half the average age of the other commissioners—named Gifford Pinchot. Also on board: Gen. Henry L. Abbot of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, a veteran of Western railroad surveys; Alexander Agassiz, curator at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology; Yale professor William H. Brewer, who was also California’s state botanist; John Muir, in an unofficial advisory capacity since he wasn’t the sort of person to join committees; and Arnold Hague.

Worst of all, as of the proclamation, the commission still had not decided the purpose of forest reserves. So these lands, like the 12 other new reserves, became off limits to use. As a result, Cleveland’s proclamation created a serious backlash in Western states.

Worst of all, as of the proclamation, the commission still had not decided the purpose of forest reserves. So these lands, like the 12 other new reserves, became off limits to use. As a result, Cleveland’s proclamation created a serious backlash in Western states. Yet the fact that reserves were no longer extensions of national parks also demonstrated their potential. Through the first decade of the new century, after Roosevelt ascended to the presidency in 1901, Roosevelt and Pinchot continued to clarify the utilitarian philosophy of the “multiple use” system—and greatly expanded the nationwide scope of protected lands.

Yet the fact that reserves were no longer extensions of national parks also demonstrated their potential. Through the first decade of the new century, after Roosevelt ascended to the presidency in 1901, Roosevelt and Pinchot continued to clarify the utilitarian philosophy of the “multiple use” system—and greatly expanded the nationwide scope of protected lands.![Land surveyor Billy Owen was was still in his teens in 1878 when he saw the solar eclipse from the top of Medicine Bow Peak in southern Wyoming. Decades later, he recalled the onrushing moon shadow: '[Terrifying, appalling .. yet [it] possessed a 'majestic grandeur and fascination.' American Heritage Center.](http://www.wyohistory.org//sites/default/files/styles/small/public/eclipse1.jpg?itok=KdHHrt0n) Worldwide, solar eclipses occur relatively often, at a rate of two to five per year. In a solar eclipse, the moon passes between the earth and the sun, sometimes blocking part of its light and at other times, all. A complete blockage is a total eclipse, and the zone of the earth traversed by the moon’s shadow is called the path of totality. The width, length and route of the path all differ from one eclipse to the next.

Worldwide, solar eclipses occur relatively often, at a rate of two to five per year. In a solar eclipse, the moon passes between the earth and the sun, sometimes blocking part of its light and at other times, all. A complete blockage is a total eclipse, and the zone of the earth traversed by the moon’s shadow is called the path of totality. The width, length and route of the path all differ from one eclipse to the next.

Draper was a pioneer, perhaps the first, in the young science of astrophotography. He planned to photograph the corona, and delegated other important observations to his colleagues. Draper reported their findings in the September 1878 American Journal of Science and Arts.

Draper was a pioneer, perhaps the first, in the young science of astrophotography. He planned to photograph the corona, and delegated other important observations to his colleagues. Draper reported their findings in the September 1878 American Journal of Science and Arts.

The men drilled from 7:30 a.m. until 10:00 p.m., with breaks for lunch, supper and an evening walk. All the expeditions performed similar drills, day after day, to perfect their routine so no time would be wasted during the brief totality.

The men drilled from 7:30 a.m. until 10:00 p.m., with breaks for lunch, supper and an evening walk. All the expeditions performed similar drills, day after day, to perfect their routine so no time would be wasted during the brief totality.

The Star goes on to describe the “wonderful clock-driven heliostat” owned by the Yerkes Observatory, of the University of Chicago. The heliostat—a mirror geared to a clock in order to continue reflecting the sun’s light at a single target as the sun moves through the day—threw the sun’s rays into a horizontal telescope and kept the light “steadily in one direction, without deviation for any length of time,” The Star reported.

The Star goes on to describe the “wonderful clock-driven heliostat” owned by the Yerkes Observatory, of the University of Chicago. The heliostat—a mirror geared to a clock in order to continue reflecting the sun’s light at a single target as the sun moves through the day—threw the sun’s rays into a horizontal telescope and kept the light “steadily in one direction, without deviation for any length of time,” The Star reported.

Five teams of professional archaeologists from three universities, together with amateur explorers, have studied areas in the

Five teams of professional archaeologists from three universities, together with amateur explorers, have studied areas in the  George C. Frison, professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of Wyoming, conducted an archaeological survey of the Bridger-Teton National Forest in field season 1974. Frison and his team found 33 sites including two fire pits, plus soapstone—more formally known as steatite—vessels, stone choppers and more than two dozen styles of projectile points.

George C. Frison, professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of Wyoming, conducted an archaeological survey of the Bridger-Teton National Forest in field season 1974. Frison and his team found 33 sites including two fire pits, plus soapstone—more formally known as steatite—vessels, stone choppers and more than two dozen styles of projectile points.

“It was thrilling to put so much effort into a project and to have it work out so successfully,” Stirn writes. “That [first] summer of exploration and discovery was one of my most memorable and exciting in a decade of alpine archaeology.”

“It was thrilling to put so much effort into a project and to have it work out so successfully,” Stirn writes. “That [first] summer of exploration and discovery was one of my most memorable and exciting in a decade of alpine archaeology.” “[M]ost tools used by past cultures were probably made of organic material,” Stirn notes, “and haven’t survived over the years. So, when we do find an ice-patch artifact it is especially exciting because it provides a rare glimpse into the past that we don’t normally get to witness.” Stirn explains that this is one reason archaeologists “are particularly alarmed at the extent that ice in Wyoming is disappearing, along with the fragile archaeological information preserved within.”

“[M]ost tools used by past cultures were probably made of organic material,” Stirn notes, “and haven’t survived over the years. So, when we do find an ice-patch artifact it is especially exciting because it provides a rare glimpse into the past that we don’t normally get to witness.” Stirn explains that this is one reason archaeologists “are particularly alarmed at the extent that ice in Wyoming is disappearing, along with the fragile archaeological information preserved within.”

In 1915, Henry and Fay Mitchell moved to

In 1915, Henry and Fay Mitchell moved to

By 1981, Mitchell was guiding groups of hikers in the Wind Rivers, outpacing many younger people and choosing the trails. During the 1980s, more publications, including Union Pacific Info, Rocky Mountain Magazine and Audubon featured stories about Mitchell. He went on more speaking tours and won more awards, including honors from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Izaak Walton League and honoraria from the state senates of Wyoming and California. In the 1990s, Western Wyoming Community College in Rock Springs dedicated its dining room to Finis and Emma. In 1992, Sports Afield published an article about him.

By 1981, Mitchell was guiding groups of hikers in the Wind Rivers, outpacing many younger people and choosing the trails. During the 1980s, more publications, including Union Pacific Info, Rocky Mountain Magazine and Audubon featured stories about Mitchell. He went on more speaking tours and won more awards, including honors from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Izaak Walton League and honoraria from the state senates of Wyoming and California. In the 1990s, Western Wyoming Community College in Rock Springs dedicated its dining room to Finis and Emma. In 1992, Sports Afield published an article about him. In 1877, employees of the

In 1877, employees of the

About six weeks previously, the party had launched its boats from the town of Green River on the

About six weeks previously, the party had launched its boats from the town of Green River on the  His wife, Emma, the party’s ornithologist and the only woman in the group, proved as hardy as the men; when the party climbed the rough trail up Pike’s Peak on July 27 and 28, she kept up easily. She went along the next year as well on Powell’s second and longer expedition, again through the Rocky Mountains and this time across the western slope. During these two journeys, Powell began to plan his trip down the Green and Colorado Rivers for spring and summer 1869.

His wife, Emma, the party’s ornithologist and the only woman in the group, proved as hardy as the men; when the party climbed the rough trail up Pike’s Peak on July 27 and 28, she kept up easily. She went along the next year as well on Powell’s second and longer expedition, again through the Rocky Mountains and this time across the western slope. During these two journeys, Powell began to plan his trip down the Green and Colorado Rivers for spring and summer 1869.

For the logistics of development, he stated in the Report that small, local water districts were best. He proposed self-governing, cooperative groups of about nine ranches or farms whose occupants actually used the water. He further recommended political divisions, such as county lines, based on watersheds and the resulting use of water in those areas. Non-irrigable areas, he decided, should not be settled.

For the logistics of development, he stated in the Report that small, local water districts were best. He proposed self-governing, cooperative groups of about nine ranches or farms whose occupants actually used the water. He further recommended political divisions, such as county lines, based on watersheds and the resulting use of water in those areas. Non-irrigable areas, he decided, should not be settled. About three months before Powell died, on June 17, 1902, President

About three months before Powell died, on June 17, 1902, President

At first reluctant to talk, they finally revealed the bag’s contents to Roberts—rough diamonds, a lot of them, all from a fabulous gem field somewhere in the West’s vastness. They refused to discuss the location. Roberts agreed to absolute secrecy, a promise he immediately broke, telling two other men about the gems: William C. Ralston, founder of the Bank of California, and Asbury Harpending, an adventurer and one-time would-be Confederate swashbuckler.

At first reluctant to talk, they finally revealed the bag’s contents to Roberts—rough diamonds, a lot of them, all from a fabulous gem field somewhere in the West’s vastness. They refused to discuss the location. Roberts agreed to absolute secrecy, a promise he immediately broke, telling two other men about the gems: William C. Ralston, founder of the Bank of California, and Asbury Harpending, an adventurer and one-time would-be Confederate swashbuckler. By 1870, both Ralston and Harpending were promoting a new project called the Mountains of Silver in New Mexico; Harpending at that time was in England seeking overseas investors. The two men were as enthralled as Roberts by the gem field story, and Harpending told a friend in London that he must “hurry home, as ‘they had got something that would astonish the world.’” And hurry he did, arriving back in San Francisco in May 1871.

By 1870, both Ralston and Harpending were promoting a new project called the Mountains of Silver in New Mexico; Harpending at that time was in England seeking overseas investors. The two men were as enthralled as Roberts by the gem field story, and Harpending told a friend in London that he must “hurry home, as ‘they had got something that would astonish the world.’” And hurry he did, arriving back in San Francisco in May 1871.

The entire affair was arguably the biggest swindle in the history of the frontier West. Arnold and Slack had “salted” the mesa, which straddles the Wyoming-Colorado border about 44 miles south of

The entire affair was arguably the biggest swindle in the history of the frontier West. Arnold and Slack had “salted” the mesa, which straddles the Wyoming-Colorado border about 44 miles south of

J. J. Hunt, operating out of Fort Steele, reported he had killed 900 elk and antelope in the winter of 1868-69.

J. J. Hunt, operating out of Fort Steele, reported he had killed 900 elk and antelope in the winter of 1868-69.

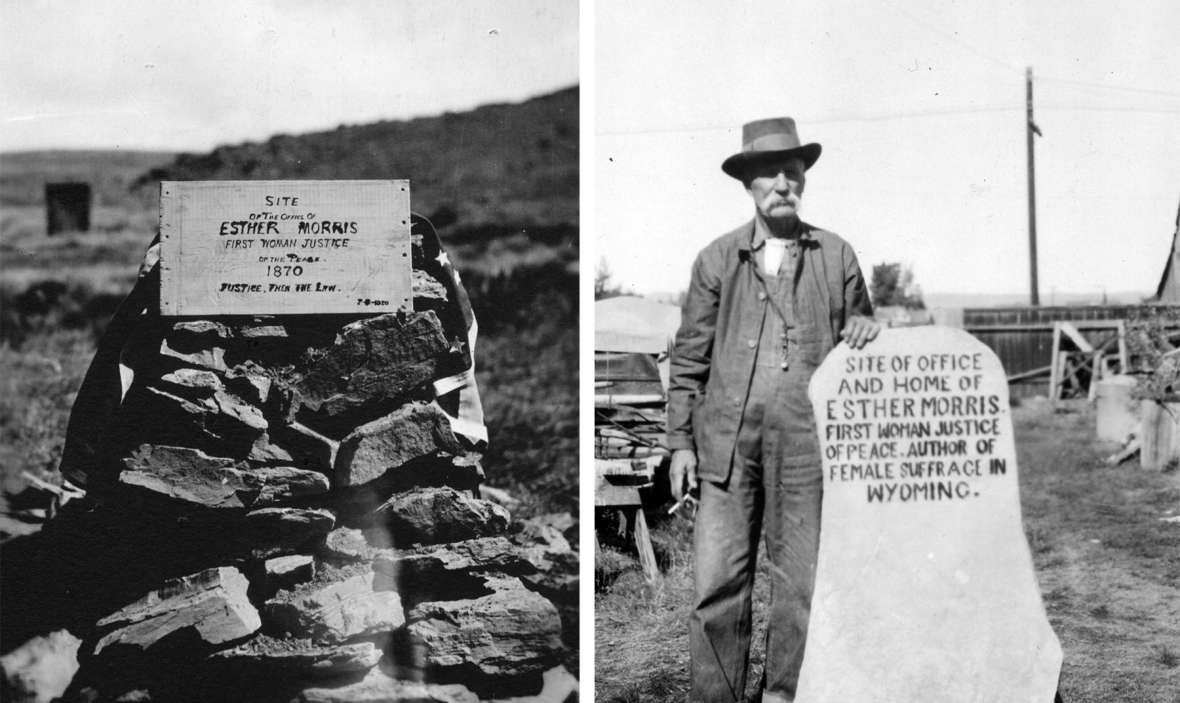

![Esther Hobart Morris was in her late 50s when she was appointed justice of the peace in South Pass City, Wyoming Territory, in 1870. '[I]n performing these duties I do not know as I have neglected my family any more than in ordinary shopping,' she wrote the following year, 'and I must admit that I have been better paid for the services rendered than for any I have ever performed.' Wikipedia.](http://www.wyohistory.org/sites/default/files/styles/small/public/morris1_0.jpg?itok=mu8GVAGA)